It Happened To Me: I Almost Dated A Sexual Deviant

Plus: Jane's Question For You

Happy Saturday (or whatever day you are getting around to reading this). Since we are running another installment of our It Happened To Me series today (the same series I started in the first issue of Sassy magazine in 1988 - yes, NINETEEN-EIGHTY-EIGHT), I have two quick notes for you:

First, we would love to run your It Happened To Me also and will pay a whopping $50 for the privilege. Send them to me, jane@anotherjaneprattthing.com. I will get back to you so fast, you won't believe it.

Second, a question for you: Are you sick of reading so many of these It Happened To Me stories and getting them in your inboxes? I would love to know.

Love always, Jane

By Sherry Shahan

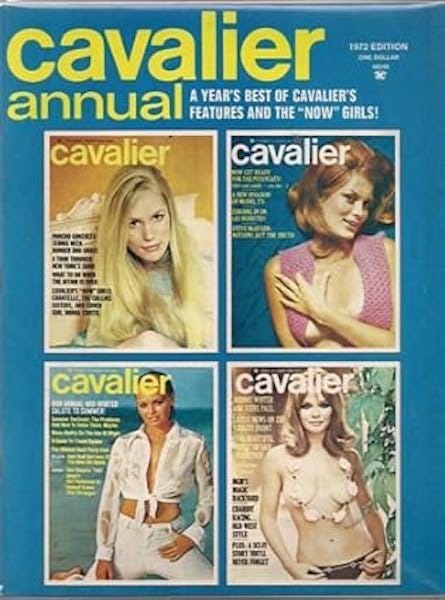

I once heard that beloved children’s novelist Judy Blume began her career by writing erotic fiction for men’s magazines. I wanted to write children’s books, too. So I perused the Adults Only rack at the liquor store, flipping through pages of Penthouse, Hustler, Adam, and Cavalier. At the time, the connection made sense. Besides, I needed the money.

Thus began the experimental phase of my fiction journey. My short stories were tongue-in-cheek tales told in the first person from a female perspective. “Long Balls and Driving Shafts” featured a pro golfer (my ex) and a cocktail server at a country club (the reason we’re exes).

It was the late 1970s. I was finishing my Bachelor’s in Social Science at California Polytechnic State University. A professor in my department mentioned an opening for a research assistant at Atascadero State Hospital (ASH), a maximum-security facility that housed Mentally Disordered Sex Offenders (MDSOs).

“Make an appointment with Dr. Richard Laws,” he said from a desk with a mountain of powder-blue essay books. “He’s the psychiatrist in charge of, um, an interesting project.” Dr. Richard Laws co-authored several academic books, perhaps the most well-known being Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment (with William T. O’Donohue).

I was careful about what I chose to wear for my interview, not wanting to attract the attention of the 1,000-plus men in the facility. I wore loose slacks and a plain Jane blouse buttoned to the neck. I wore basic makeup, but no jewelry.

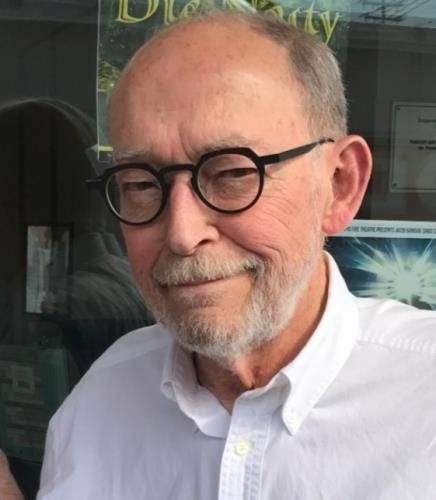

Dr. Laws’ pioneer research gauged interventions for deviant and harmful sexual behavior. I met the Director of the Sexual Behavior Laboratory (who held the job from 1970-1985) in his cluttered office. He looked like I’d expected: a living cliché. Eager, yet composed. Thinning gray hair and a manicured beard. Black-rimmed glasses on a dagger nose.

“Tell me about your writing.” He grew still, waiting. I told him about the short story I was working on—a middle-aged couple having sex in a dentist’s office. “ ‘Open wide’ has a double meaning.”

I got the job.

Part of being a writer is being curious. I like to poke around, ask difficult questions, keep track of things. Over five years, hundreds of employees at ASH suffered injuries from being attacked by patients. Some had been assaulted more than once.

I was issued a “panic button” in case of a threat or assault. The gizmo was the size of a pack of cigarettes and hooked onto my waistband. I imagined a muscled guard bounding down an endless corridor to rescue me. At 5’3” and 110 pounds, I’d be in serious trouble before he took his first step.

My girlfriends called these men scumbags and sick fucks. The staff was adamant. “This is a hospital, not a prison. These are patients, not inmates.”

Words shaping impressions?

Even with an escort, the hospital—an imposing facility with a labyrinth of private rooms and four-person dorms—unnerved me. The walls were either cinder blocks or poured concrete, and the beds were thin sleeping pads on ledges.

The men wore khaki uniforms and laminated name badges. They wore no belts or shoelaces (to hang or strangle). Their downturned faces were the color of paste. The air was thick with shame.

Someone hummed Queen’s, “Another One Bites The Dust.”

Alarms constantly buzzed in my head because I couldn’t tell the difference between a Peeping Tom and a child molester or a serial rapist.

My first assignment was writing four-page scripts—each with a different scenario from the perspective of a female being sexually assaulted. Dr. Laws played the audiotapes in a private room in his lab for rapists who’d volunteered to be in his study.

To me, ‘volunteer’ seemed like a loaded word. Many, no doubt, participated to show staff their willingness to change their deviant behavior. I was not privy to the research results.

After writing scripts, I spent most of my time in the laboratory, which consisted of three interlocking rooms, all with thermostats set too low. There was a lack of smells, strange for a hospital.

Well-thumbed men’s magazines fanned across a table in the cramped entry area. I frequently checked the table of contents for my by-line. Until working at ASH, I hadn’t thought about the men who read my short stories.

###

The equipment in the lab was mammoth and resembled a giant lie detector.

The official name of the machine is penile plethysmography or phallometry—developed by Kurt Freund in the 1950s to assess sexual or erotic preference for children versus adults.

In private, we called it the ‘Peter Meter.’

Dr. Laws’ assistant wore a white lab coat, smelled vaguely of cigarettes, and reminded me of Debra Winger in Terms of Endearment. She adjusted gauges and dials while explaining how to use them.

“This is a transducer and filled with mercury,” she said, waving a rubber band-like thing. “It fits over the base of the patient’s penis.”

Startled, I took a stutter-step backward. “What?”

“Don’t worry.” She laughed, though completely serious. “They put it on themselves. It’s connected to the machine and measures the flow of blood, which in turn determines the amount of sexual arousal.”

The particular research program at this specific time dealt with pedophiles.