It Happened To Me: My Friend's Sexual Assault Changed My Life

I thought I’d put my prep school years behind me, but the election brought back an ugly memory: My favorite teacher, the girl from my neighborhood, and the weight of silence.

By Seth Lorinczi

“Revenge of the Me-Too Martyrs,” reads one headline; “Men Always Win” another. If you haven’t noticed, it’s not a great moment for women. Sexual violence — and the official silence that helps enable it — has always existed. But the current crop of Senate confirmation hearings — thus far only one of President Trump’s three nominees accused of sexual misconduct has been forced to withdraw owing to the flagrance of his offenses — brought me back to my own childhood in Washington, D.C. some 40 years ago.

Back then I attended a prep school very similar to (in fact, just a few miles from) the ones Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Christine Blasey Ford went to. When I was 13, another act of sexual violence and institutional silence — involving a childhood friend and my favorite teacher — changed me forever. It was the moment that turned me away from the mainstream, towards a life as an outsider. A decision that, for better or worse, I’ve had to live with ever since.

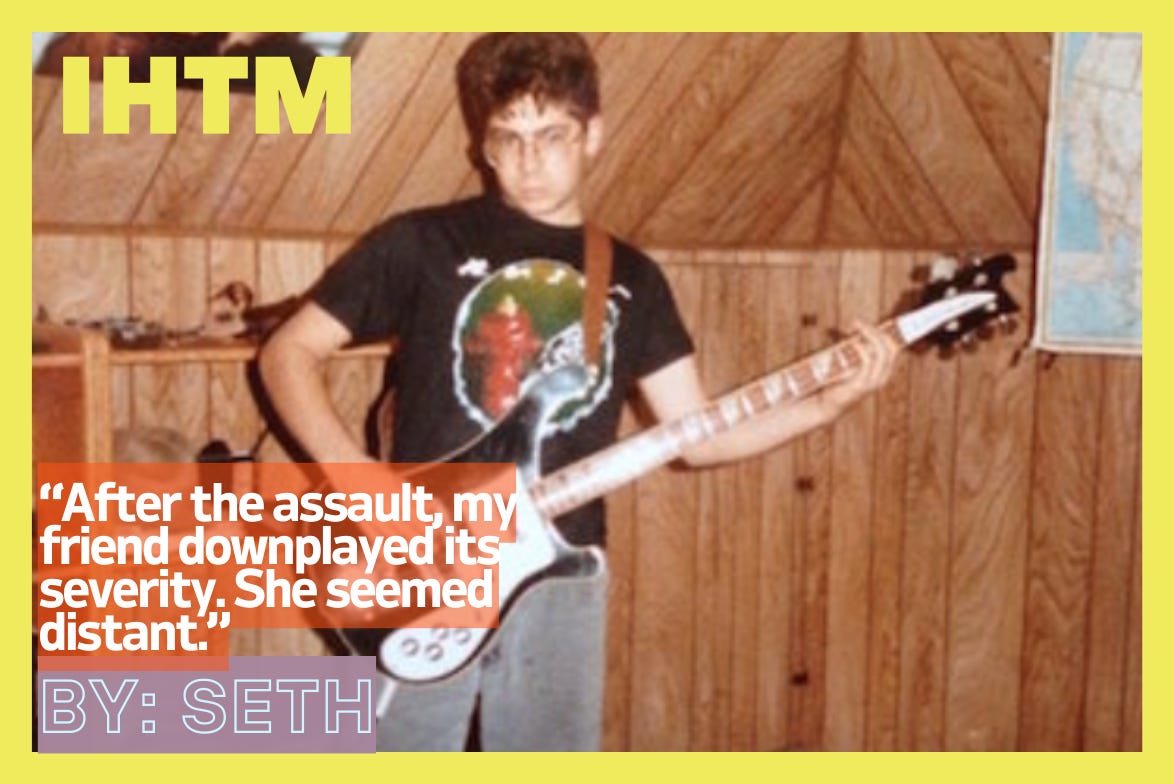

Even in a city as wealthy as Washington, St. Albans School stands out.

When it opened in 1909, St. Albans’ mission was to educate the boy choristers of the Washington National Cathedral, the towering landmark on whose grounds the school sits. As its prestige grew, the school began to attract a tonier clientele: future congressmen, astronauts, media figures athletes, and a Vice President (Al Gore). Today, the students, all male, dine in a “refectory,” not a cafeteria. They’re grouped by “forms,” not grades. The dress code mandates English-style blazers and ties.

St. Albans is a classic prep school, though in hindsight I wonder exactly what it’s prepping its students for. I do know this much: I didn’t belong there. If I thought those starchy uniforms were supposed to make us all equal, I soon learned otherwise. Sensitive, unathletic, and Jewish, I quickly sank to the lowest rungs of the pecking order.

Given the pride placed on both athletic and academic achievement, the halls were fairly awash in testosterone. The school faced the issue squarely, subjecting all boys in A Form (that’s sixth grade) to a laughably counterfactual sex ed supplement given by “Coach,” a terrifying, ramrod straight man rumored to have been the Army’s first Black drill sergeant (he wasn’t). As he barked through his lecture, explaining that morning erections (“piss hards”) were instigated not by REM sleep but by an excess of urine, I struggled — and failed — to stifle my giggles. It’s safe to say that Coach loathed me.

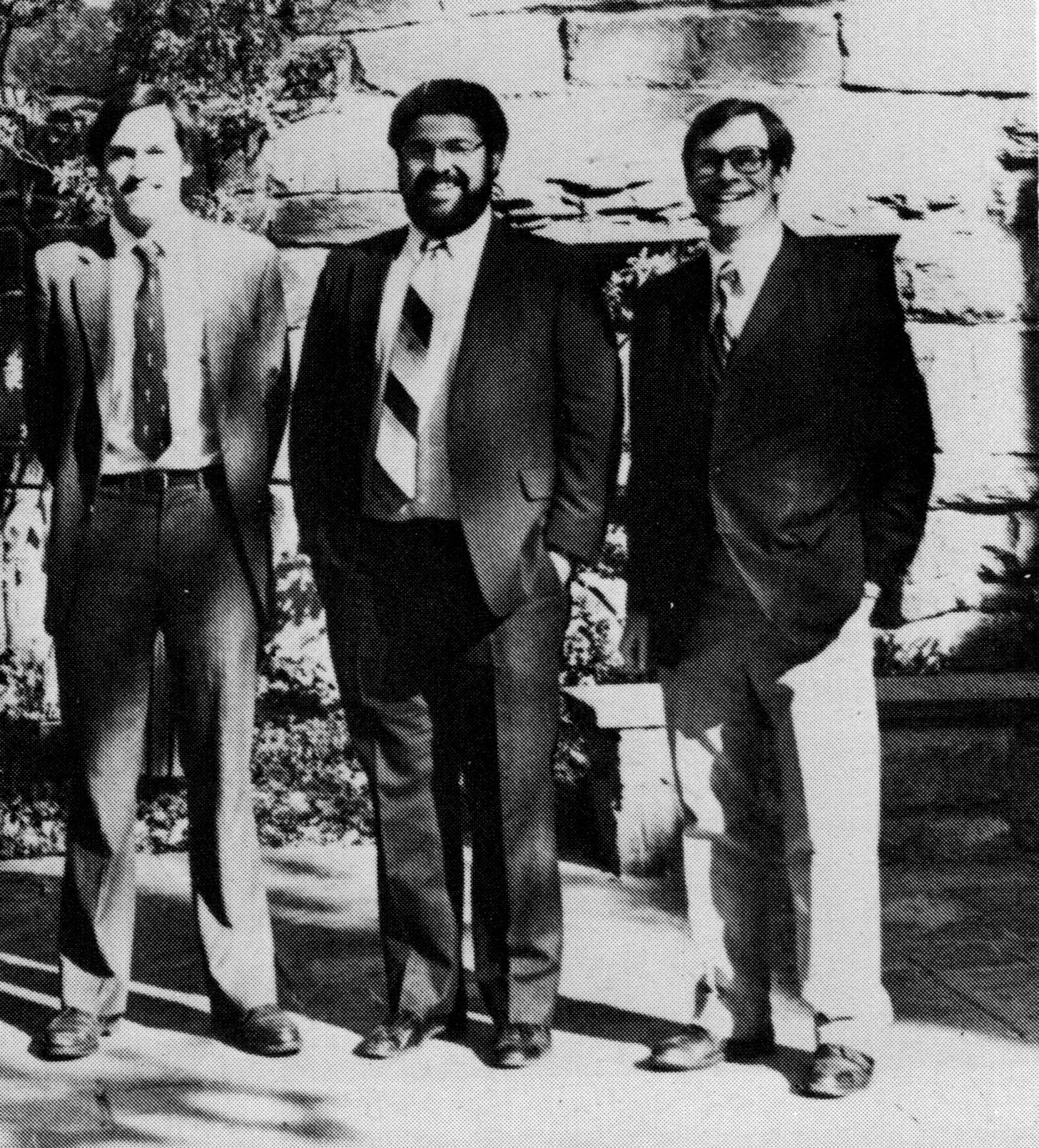

The class, held in the school’s cramped, peak-roofed attic, was a literal apex of discomfort. But downstairs, in the basement of the Lower Form building, I found some relief: Mr. Wilmore’s class. Ron Wilmore taught English. If Coach was rigorous and upright, Wilmore was a big bear of a man, prone to broad ‘70s-style ties a full four years into the Reagan Era. He was also one of the more popular teachers at St. Albans and, unlike his prudish colleagues, he wasn’t afraid to talk about sex. One day, as we read Robert Peck’s “A Day No Pigs Would Die,” he paused at the scene in which farmer Tanner slaps a handful of lard under a breeding sow’s tail.

“What’d he do that for?” asked Wilmore. The room grew silent. I was 12 years old — the possibilities of sexual function just dawning on me — and I felt my face grow flushed. When one student gingerly raised his hand and suggested it was to ease the animal’s sexual congress, Wilmore nodded sagely. It felt like an initiation into something edgy. Mr. Wilmore was cool! He wasn’t afraid of the truth! I trusted him, and I wanted him to like me.

There was one other person who I wanted to like me: My neighbor, Marnie.

Marnie lived a couple of blocks away from me. While I doubt her family was as wealthy as some of our neighbors, trust me, you’d recognize their name. A slight, fair girl with a moon face and large eyes, Marnie was an intellectual in a family that prized cerebrality. She was also, I see now, almost unbearably sensitive. Those big eyes telegraphed what seemed like near-constant worry.

My feelings for Marnie weren’t exactly romantic, but I felt drawn to her. Like Wilmore, she seemed to at least tolerate my anxiety and awkwardness. I cherished the few moments I’d see her, walking home from the bus stop or around the neighborhood. She seemed to have a heart for tender animals such as myself.

Marnie and Wilmore knew each other, too. She attended National Cathedral School (NCS), St. Albans’ feminine counterpart; he was the faculty advisor to the Literary Club, one of the few sanctioned activities where boys and girls could mingle. Given her sensitivity and intelligence, I imagine she was one of Wilmore’s star pupils. I don’t know the nature of their relationship, whether he gave her rides home after club meetings — a not uncommon practice at the school. But I do know this: In 1983, when Marnie was preparing to enter ninth grade, she attended a Literary Club picnic with Wilmore. At some point in the festivities, he drew her aside, away from all the other attendees, and then he raped her.