Sleazy Times Square, 24-Year-Old Jane Pratt, and Me

Working at Sassy helped me grow up — and deal with my sister’s death.

A few weeks ago, Christina Kelly and I had lunch with original Sassy staffer Elizabeth Larsen while she was visiting New York. One of the many beautiful things that came out of that fun reunion - where we talked about things like our kids who are now the ages we were when we started Sassy - was this essay. I hope you love it, whether you were a Sassy reader or not. Let me know, of course. -Jane

After I graduated from college, I traveled for three months across South America. On my first Sunday back in New York, I flipped to the “Help Wanted” section of The New York Times, because this was 1987. The editor of a soon-to-be-launched teen magazine needed an assistant. I went to a copy shop to print my resume and cover letter and put them in the mail.

A few days later, I returned home to see the message light flashing on the answering machine. It was from a woman named Jane Pratt. She wanted me to come to her office at 1 Times Square for an interview. Her voice was warm and encouraging, with a trace of a Southern accent. She said she was looking forward to meeting me.

Even though the building at 1 Times Square was famous for dropping the ball on New Year’s Eve, back then it was a dump of an office tower in a part of the city that was known for junkies, prostitutes and the theater where you saw “Cats.” When I arrived at Jane’s office, the reception area was piled with moving boxes. The walls were painted a fresh coat of light pink, but the only decor was a worn-out armchair and a side table with a stack of prototypes of the magazine she was starting. It was called Sassy.

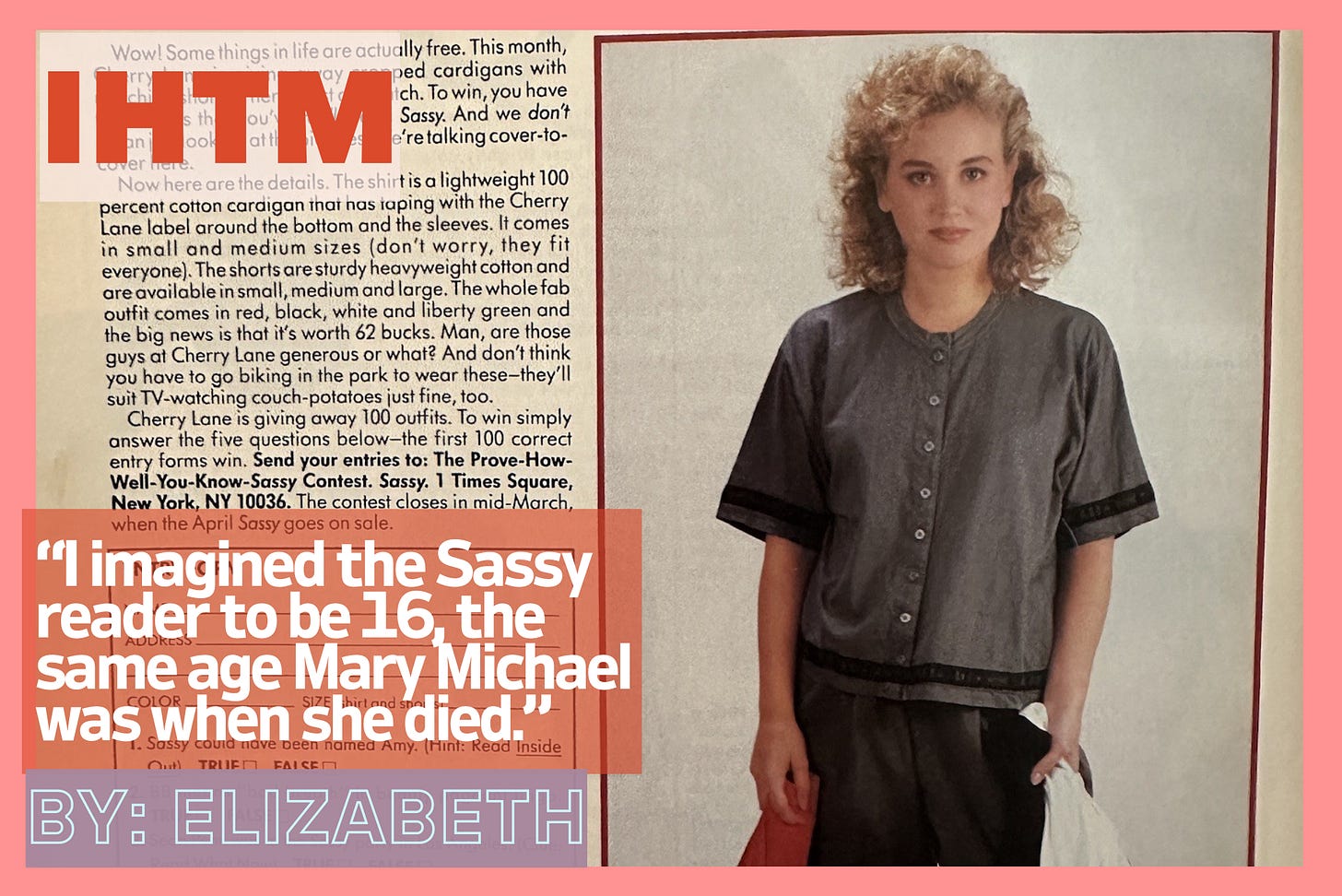

Sassy was owned by Fairfax, an Australian publishing company, who modeled the prototype after a magazine called Dolly, which apparently had one of the highest readerships of any teen magazine in the world. The language in the prototype was relaxed and slangy, like a conversation between close friends. I’d subscribed to Seventeen when I was in middle school. Until that moment in the reception area, I hadn’t realized how maternal it felt, how out of touch it was with the reality of American teenage life, with stories about how to host themed parties and choose boyfriends your parents would like.

The Sassy prototype, on the other hand, assumed teenagers were having sex. There was no moralizing about what the reader should do. Instead, there was honest and trustworthy advice about birth control, sexually transmitted diseases, and making choices that promoted self-care and self-esteem. Plus, fashion that was actually stylish and beauty tips that urged the reader to go easy on the makeup. In all my women’s studies courses, I’d never come across something that combined a feminist agenda with so much fun. There was room on these spreads for fashion and advice for how to not be so devoted to your boyfriend that you lost sense of who you were. The teachers from my all-girls elementary school would have loved it.

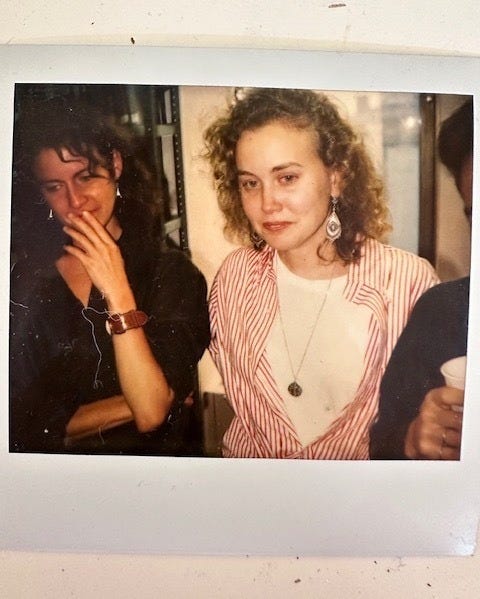

Jane invited me into her office and welcomed me with a hug. She was wearing worn-out black brogues and socks that were loose around her ankles. Her hair was dyed auburn and she had thick, straight bangs—an alt rock version of Audrey Hepburn. I can’t remember what I was wearing but I’d been living in New York for three years and had picked up on what was in style for women in their twenties. I’d saved up some babysitting money to buy a cardigan from Agnès B. that was made of sweatshirt material and had snaps up the front. I paired miniskirts with granny boots. I had my own look, but Jane lived in a new category of hip.

I’m not sure Jane even had time to sit at her desk before I blurted out how much l loved the magazine.

“I’d do anything to work here,” I said,

“I’d do anything to work here,” I said, pressing the prototype to my chest. Then I explained that I knew how to fact check.

“How are you with organization?” she asked. “My assistant will have to do a lot of clerical stuff, like submit expenses.”

“Pretty good,” I lied, thinking of the stack of unpaid utility bills on the hallway table in Ginia's and my apartment.

I had never taken a journalism class, had never written a single word for publication. I needed to steer the conversation away from my lack of skills or I’d never get this job. I’m not sure why I thought the most catastrophic loss of my young life would help my chances, but I suddenly found myself oversharing.

“My sister died three years ago,” I said. “She was 16. Leukemia.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Another Jane Pratt Thing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.